Liberal landslide: the 1906 election

In 2006 I gave a talk at a dinner to mark the 100th anniversary of the 1906 Liberal landslide election victory, drawing parallels between elections now and then which are still very relevant. These are the slightly edited notes I spoke from.

Imagine you are Prime Minister, with a majority of 130 (and in practice a majority of more like 350 on most issues given how small the main opposition party was). You call a general election on a point of principle and end up not merely without a majority but in fact 60 seats short of having even a majority of just one.

Not perhaps a very impressive result.

Yet this was what happened in 1910. Within four years, the 1906 Liberal landslide was gone and the Liberals were dependent on other parties in order to stay in office.

Yet this was what happened in 1910. Within four years, the 1906 Liberal landslide was gone and the Liberals were dependent on other parties in order to stay in office.

Before saying something about how 1906 happened, it is perhaps worth reflecting on this uncanny parallel with that other great landslide government – Labour’s 1945 government.

It too started with a huge majority – 146 in 1945 – but by 1950 shrunk it to a tiny majority of just 5 – and within 20 more months the Tories in government.

So, although both the 1906 and 1945 governments are regularly labelled great, I’m sure you will understand why I – from the party’s Campaigns and Elections Department – would rate them slightly less great!

Doubtless, Lloyd George and Attlee didn’t deliver enough leaflets.

(Actually, if you were to ask me which politician of the 20th century was least likely to have delivered Good Morning leaflets, I think Attlee would have been near the top of the list).

One aspect of 1906 appeals rather more to the party campaigner in me. Years later, Herbert Gladstone boasted as to how he made a profit for the Liberal party on the campaign. And not just a small profit – the campaign had cost £100,000 but he had raised £275,000 – a profit of £175,000. In modern money that is a cost of around £8.5 million and a profit of nearly £15 million.

Who needs loans…?

Though actually there was a fair degree of controversy over the fundraising techniques of both Liberals and Tories in the early twentieth century, even well before Lloyd George got to work. Both Liberal leader Campbell-Bannerman and the Conservative Prime Minister Balfour before him were accused of using honours to reward those who had donated to party funds.

But – back to 1906 and 1945. These two governments do form an interesting contrast from Tony Blair’s search for his historic legacy. For all his soul-searching about securing such a legacy, he seems to have missed the point that these two great governments were great – and had their legacies – precisely because their majorities were seen as a means to an end (ends which required radical, often controversial, policies) rather than seeing their majorities as something to be retained at all costs. Winning elections was for these governments, a means to an end – not the end itself. Yet for Blair after his 1997 victory, his huge majority often seemed a burden – the obsession with retaining a big majority restricting his actions and cramping his style rather than freeing him up to make those bold moves which generate historic legacies.

Anyway, back to the Liberals. The scale of the 1906 landslide – in which all but three of the previous Tory Cabinet were defeated – was rather exaggerated by the vagaries of Britain’s first past the post electoral system. Although it was a landslide in terms of seats, the Liberals only polled 300,000 votes (6%) more than the Conservatives. But thanks to the Gladstone-Macdonald Lib-Lab electoral pact the seats gained by the anti-Tory vote were maximised. Labour benefited too from a dramatic growth in the number of its MPs as the number of Tory seats was greatly diminished by these tactical arrangements.

And, it was certainly a dramatic landslide – with diners in the National Liberal Club dancing on the tables as victory after victory was reported. Elections – I should explain – took place over several days at the time.

Even the former Tory Prime Minister, Balfour, was defeated. He was, however, able to quickly return to Parliament thanks to a safely re-elected Tory MP resigning his seat to create a by-election. An option I’m sure a few of our candidates last year would have wished was open to them!

Now – all this was a dramatic contrast from just a few years before. The leader of the Liberals, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, had not had a good previous election – the 1900 election was a Tory landslide, following as it did promptly after a series of military victories that had appeared to bring an end to the Boer war in southern Africa.

The Liberal Party had been deeply split over the war. It had both pacifist, anti-empire members and also those who were happy to go with the much more popular line of supporting the empire and its expansion.

Campbell-Bannerman supported the empire’s armed forces but attacked the Government for starting the war and particularly attacked their methods (a familiar-sounding combination to modern Lib Dem ears, I’m sure). The methods in contention then were the burning of farmsteads and use of concentration camps, which he attacked coining the famous phrase, “methods of barbarism”.

It was only the ending of the war in 1902 that allowed the Liberals to overcome their divisions as the war’s end largely removed the issue from the political agenda. In as much as the war was still an issue, it became a burden for the Tories as questions were asked about its conduct despite the military victory (shades of Iraq again). Military failures and organisational blunders were increasingly blamed on the Tories. How had it taken so many years for an international empire to win one military conflict in a small part of the world?

Attempts to answer this question – and prevent similar problems in future – caused deep splits in the Tories.

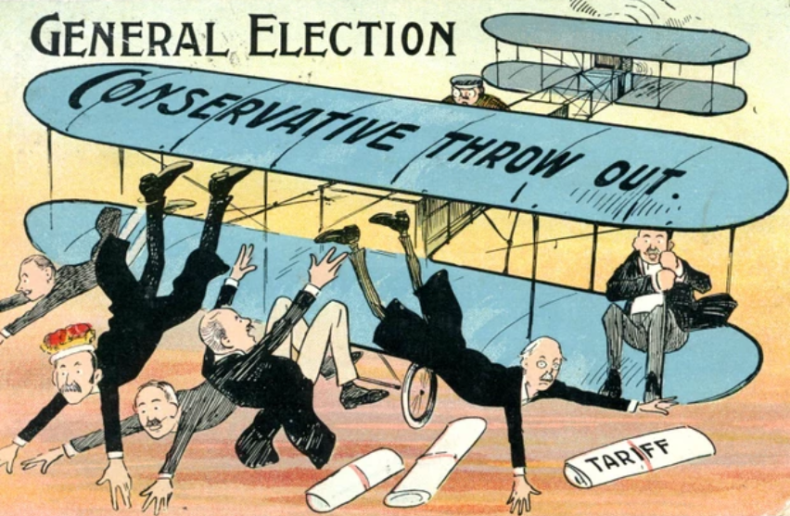

Some Tories, led by Joseph Chamberlain, believed that the answer to these weaknesses of empire was to bind the empire more closely and effectively with a system of tariff reform that would give colonies preferential trading treatment. This repudiation of free trade caused great splits in the Tories.

Much of this was due to the brash promotion of tariff reform by Chamberlain, who almost single-handedly put the issue centre political stage, making politics about this – the issue he cared about –rather than any other issue. He breezily told the Liberal Chief Whip before his seminal Birmingham speech on the subject that: “You can burn your leaflets. We are going to talk about something else”.

His confidence, bordering on arrogance, that he could change the course of political debate in the country proved correct – it did become the big issue of the day, but it also deeply split his party.

(It was, by the way, the issue which triggered Winston Churchill’s switch from Tory to Liberal in 1904).

In contrast to these Tory problems, the free-trade Liberals were united and able to work together once more, having been given a common and high profile cause to rally around. As an added bonus, supporting free trade was not only unifying for the Liberals – it was also very popular with the public. Indeed, Asquith’s response to reading a report of Chamberlain’s Birmingham speech was, “Wonderful news today and it is only a question of time when we shall sweep the country.”

Supplementing the impact of free trade was religion. Two particular disputes – over education and licensing – energised Nonconformists in their opposition to the Conservatives.

Eventually, the Conservative government, led by Balfour, resigned in December 1905 unable to cope with its free trade splits. Balfour hoped that putting the Liberals into power would in turn expose Liberal splits. However, the prominence given to free trade, the impact of religious issues and the pressures of office served to unify rather than divide the Liberal party. They were aided in this by the skilful leadership of Campbell-Bannerman, who deftly managed the different factions and personalities. He did this in a rather subdued – almost Atlee like way – managing effectively rather than leading dramatically.

This style was partly a reflection of his age. He was 69 when he became Prime Minister – and was, in fact, was the only serving Prime Minister who at the same time was the oldest MP in the Commons.

The first few hours of his government were rather farcical for, on the day the various Cabinet ministers went to see the King to receive their seals of office, London was shrouded in a very thick fog – thick even by the standards of the time. Real pea soup stuff.

On departing Buckingham Palace the Cabinet Ministers were meant to head to their new departments. Yet the fog was so thick, this was a near-impossible task. Fowler was one of a trio who hired a cab but then had to abandon it in the Mall due to the fog. After time spent stumbling around trying to get to his ministry, he eventually realised that all he had managed to do was to make it back to the gates of Buckingham Palace.

He, and the others, did eventually make it to their offices, with Campbell Bannerman as Prime Minister, leading initially a minority government. Not surprisingly, therefore, a general election soon followed.

The election campaign he led in 1906 concentrated heavily on the Tory record. Looking at his 1906 election address, he said, “In coming to a decision, the electors will, I imagine, be largely guided by the consideration, in the first place, of the record of the late Government; and, secondly of the policy which the leaders of the Unionist [i.e. Conservative] party are now submitting.”

In terms of positive policies for his Government, he went on to talk about free trade. Free trade was really the only other major issue in the election apart from the Tory record.

In recent times, support of free trade has often been portrayed as being at odds with support for the poorest in society (free trade equals job losses being the argument).

But back then, free trade’s proponents had a much more direct appeal to such people, saying that free trade was about cutting food prices. It wasn’t seen so much as threatening their jobs but rather as cutting their food bills.

Other than free trade and the Tory record, the Liberal program had little to say, with some moderate and imprecise talk about reducing taxation and talk of doing “something” about Ireland.

The measures we normally associate with the 1906 government – pensions, Lords, and so on – were peripheral to the election, though many Liberal candidates did mention support for the introduction of old age pensions.

Some aspects of the campaigning would be familiar to modern campaigners – such as in London where the Liberal Chief Whip (it was Chief Whips who organised party election campaigns and elections funds) divided the 61 London seats into three groups – 28 it could win, 10 it might just possibly win and 23 it was unlikely to win – and then concentrated financial help and party agents on those first 28. But the money came with strings – it had to be matched locally and was only given where candidates were in place. All very familiar…!

Familiar too in many ways was the volume of literature issued. The Liberal Publication Department centrally issued no less than 25 million leaflets and books – for an electorate of just over 7 million. Or more than three items for every elector in the country – and that’s not counting any literature produced outside of LPD.

Since 1906 we have had the “first TV election” and (more than once) the “first Internet election”. Well, 1906 was the first motorcar election – in which this still relatively new form of transport made a major difference to the ability of campaigners to get about and to get voters to the polls.

Quite remarkably it was estimated that approaching half of the country’s cars were pressed into election service.

Campbell Bannerman was not able to enjoy the fruits of the 1906 landslide for long. Health curtailed his premiership after just two years, during which times the government mainly concentrated on undoing various Tory measures (such as the previous education act) and traditional liberal concerns. It was only when Asquith took over in 1908 – with, perhaps as significantly, Lloyd George becoming Chancellor – that there was a significant radicalisation of the government.

It is unfair to Campbell-Bannerman to put these changes simply down to his departure. Had his health held out, he too might have overseen this radicalisation, brought on as it was by dropping public support and the repeated heavy amendment of government measures by the House of Lords. Indeed, it was whilst he was still Prime Minister that old-age pensions were first introduced in 1907, to be funded by increased general taxation on the better off. And arguably confrontation with the House of Lords over its powers would have happened under him too – he had simply been carefully building up public support on the issue and waiting for the right moment to strike.

We will of course never know what Campbell-Bannerman might have done. We do know what did happen. Asquith’s government increasingly took on the “New Liberal” policies promoted by those who wished to concentrate not just on removing obstacles to liberty but also on providing the positive social conditions which true liberty also requires, such as taking people out of poverty in old age and providing health services.

The crux of the reforms was Lloyd George’s 1909 “People’s Budget” which significantly expanded plans for old age pensions along with a series of radical tax changes, including a new higher rate of income tax and a land tax. Rejected by the Lords, it trigged a struggle for democratic supremacy – which the Liberals won. Or more accurately, the Tories and the Lords lost – because the result of that first 1910 election (and subsequent ones) was not to give the Liberals on their own a mandate. It was only in conjunction with Labour and Irish nationalists that they had the numbers to comfortably defeat the Conservatives in House of Commons votes and to get through the sequence of legislation that makes 1906 so famous, and so beloved to liberals.

One other thought about the 1906 outcome. When Asquith – an MP from Fife – became Chancellor under Campbell-Bannerman, he was given a wide brief to roam over domestic issues outside the Treasury’s immediate remit and was also seen as the obvious successor in due course.

Asquith. Campbell-Bannerman. Brown. Blair?

Doubtless Brown must pine for the very briefing period in waiting – two years – that Asquith had to serve as Chancellor!

But in conclusion, how was 1906 won?

It was won by a united party, fighting a well organised (by the standards of the day) campaign with generous financial resources and technological innovations (the motorcar). It was won largely on the record of the previous Tory governments – but also by having a very clear, distinctive policy difference. On the Free Trade versus Imperial Preference issue, it would have been very easy to tweak and fudge, “Yes, we’re the party of free trade, but there are just one or two exceptions …” But instead, the Liberals managed to draw a clear principled distinction between themselves and the Tories – and take a stance that was both highly relevant to voters and popular.

On trade, pensions and other issues, the Liberal Party managed to combine a moral argument – “we have principles and beliefs, and this is the right thing to do” with a pragmatic one – “it’s not just the right thing to do but it is also what works”.

In particular, taxing the rich to pay for (in modern terms) better public services was justified on both moral and pragmatic grounds.

Lessons which can, perhaps, be applied today.

Want to find out more about the 1906 Liberal landslide? Get A.K. Russell’s book here.

Another interesting parallel with 1906 is 1997, just 17 years after their greatest triumph the Liberals were pushed into 3rd place. Contrary to almost everyone else I predict the same will happen to Labour in 2015, if they avoid collapse.

Much enjoyed this piece, which was instructive in a number of ways. On a trivial note, it’s striking that, as far as I know, Balfour and Campbell-Bannerman were the only Cambridge-educated Prime Ministers of the twentieth century. For whatever reason Oxford has dominated, with every PM since WW2 from there except Major (no university) and Brown (Edinburgh).

It also did not include Jim Callaghan who came from a family too poor to endure a son at Uni. Sadly, he was bright enough to get an Oxford Scholarship from his Cardiff Secondary School but was never able to build on that.

Interesting analysis. It was indeed the economy, stupid: the price of food was the Liberal trump card. The Tories had already played the race card in 1904, with the essentially anti-Semitic Aliens Act – which the Liberals were not proposing to repeal – and efforts to re-run 1900 Boer War jingoism were past their sell-by date. A surprise problem for the Tories in the 1906 election was their acquiescence in ‘Chinese Slavery’ in South Africa, an issue on which the Liberals managed simultaneously to play on nonconformist distaste for indentured labour and what it did in its spare time; and to working class fear of wages being undercut by cheap competition. Racism was alive and well in Edwardian Britain.