Forgotten Liberal heroes: Clarence Henry Willcock

Listen to Liberal Democrats make speeches and there are frequent references to historical figures, but drawn from a small cast. Just the quartet of John Stuart Mill, William Gladstone, David Lloyd George, David Penhaligon corner almost all of the market, especially since Bob Maclennan stopped making speeches to party conference. Some of the forgotten figures deserve their obscurity but others do not. Charles James Fox’s defence of civil liberties against a dominating government during wartime or Earl Grey’s leading of the party back into power and major constitutional reform are good examples of mostly forgotten figures who could just as well be a regular source of reference, quotation and inspiration as the traditional quartet. So in this occasional series I am highlighting some of the other figures who have been unjustly forgotten.

“I am a Liberal and I am against this sort of thing”. With those words (reputedly) Clarence Henry Willcock, usually called Harry, refused to show his identity card to a British policeman on 7 December 1950. This triggered a sequence of events that helped cause Winston Churchill to decide to abolish identity cards in Britain, thirteen years after they were introduced as an emergency war measure in 1939 and seven years after the war had ended.

Willcock was named by Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg as one of his liberal heroes in 2007:

The liberal argument put forward by Harry and others in opposition was a fundamental one; it was an argument about liberty and the relationship between the individual and the state. For them, the imposition of ID cards was intolerable because of the power it gave to the state, a power which was inevitably abused.

Harry Willcock had been, the police said, driving his car “erratically” along Ballard’s Lane in North London when he was stopped and asked to show his identity card. Willcock was charged and convicted at Hornsey Magistrates Court both for his refusal to show his card and for his driving. He lost his appeal against the former (Willcock v. Muckle), but in making his judgement Lord Goddard criticised compulsory identity cards and warned that they “tend to make people resentful of the acts of the police”.

Willcock himself made good use of the attention his case generated, founding the Freedom Defence Committee to help the campaign against ID cards and other wartime controls and taking part in a series of publicity stunts, such as tearing up his own identity card on the steps of the National Liberal Club. His campaign was joined by others such as the British Housewives’ League.

When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister again in 1951, he abolished identity cards – with the cost-savings of doing so being stressed in an echo of twenty-first century debates – and being praised by Liberal Party leader Clement Davies for taking this action.

Willcock was not quite an ordinary person who suddenly stood up against authority and won – for he had been active and prominent in Liberal politics (and an independent councillor). Nor did opposition to identity cards start with him. However, his act of individual defiance provided a catalyst – even if the exact motivations (why then? how pre-mediated was the act?) are now lost to history.

The legacy of Clarence Henry Willcock as a campaigner is a successful one. As an election candidate it was rather less so, for he finished third as the Liberal candidate in Barking at the two general elections preceding his fame, and the ending of identity cards by a Conservative Prime Minister did not bring the Liberal Party electoral benefits.

Achieving policies without achieving electoral success is a reminder of both how campaigning outside the ballot box can bring results but also that for a political party that in itself is not enough for a successful future.

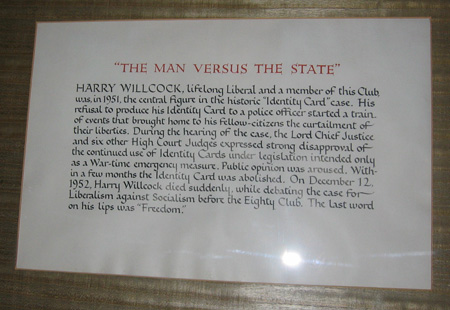

Harry Willcock is remembered in a plaque on the wall of the National Liberal Club in London:

Further reading: Harry Willcock: The Forgotten Champion of Liberalism by Mark Egan in the Journal of Liberal History.

For the other posts in this series see my Forgotten Liberal Heroes page.

Leave a Reply