How leaflets (and canvassing) raise turnout in British elections

Welcome to the latest in my occasional series highlighting interesting findings from academic research. Today – how leaflets, which we know from other research work at helping to win elections, also help to raise turnout.

(You may have seen this research before as I covered it originally in 2017. But I’ve now updated what follows as the research itself has worked its way through the academic system.)

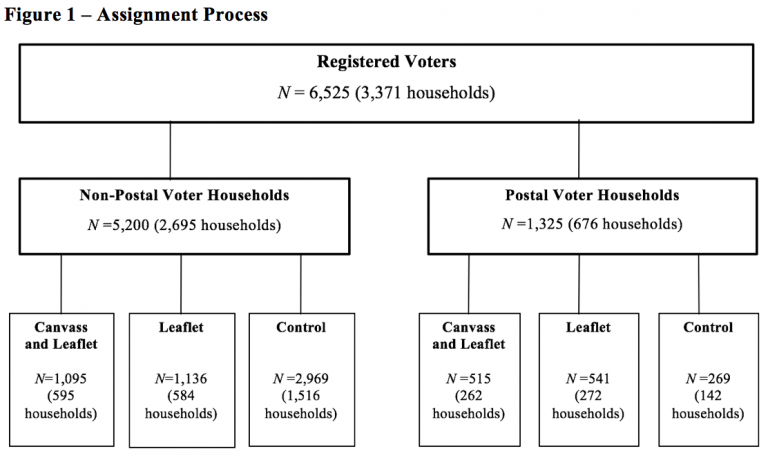

The following conclusions are from a field experiment carried out by Joshua Townsley during the 2017 local elections. Voters in a ward were randomly selected to receive either no campaign activity on behalf of the Liberal Democrats, a leaflet or a leaflet and a doorstep canvass:

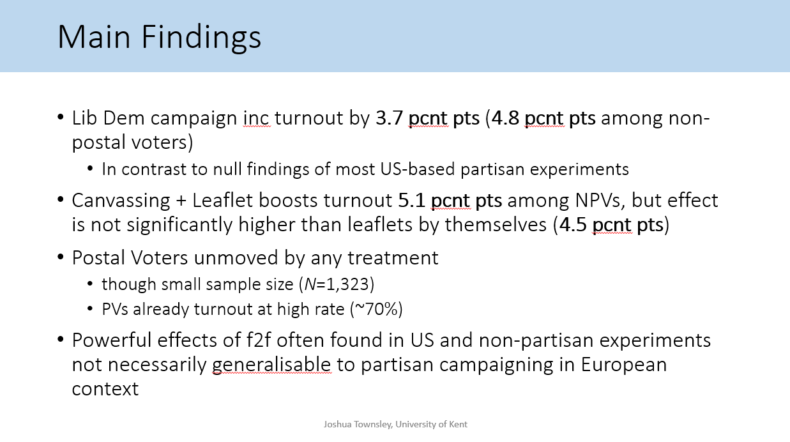

The results of this were:

(Slide taken from ‘Knock-Knock’: The role of personal contact between local parties and voters during election campaigns in Britain by Joshua Townsley, presented at EPOP 2017. PV = postal voters. NPV = non-postal voters. F2F = face to face.)

The relatively small additional impact of canvassing compared to doing just a leaflet does not necessarily mean that canvassing on its own wouldn’t have been as effective, or even more effective, than leafleting on its own.

Given the ability to leaflet more houses per hour than the number of households who can be canvassed per hour, however, the smallish additional effect of canvassing is suggestive for campaign priorities. All the more so when the finding from a field experiment previously carried out in Tower Hamlets, which showed leafleting coming out well compared with canvassing, are taken into account.

For more details on this research see, “Is it worth door-knocking? Evidence from a United Kingdom-based Get Out The Vote (GOTV) field experiment on the effect of party leaflets and canvass visits on voter turnout“, Political Science Research and Methods, 3 October 2018. The figures in the slide above have been slightly revised in this version but the overall conclusions are the same.

You can read the other posts in the Evidence-based campaigning: what the academic research says series here, including the potentially contradictory findings from a 38 Degrees experiment.

The other crucial question is of course – did those voters change their views. One problem with a lot of studies is they measure turnout (which is easy and accurate to measure) rather than the impact on changing voting intention.

It’s interesting what it says about postal voting. I always thought a lot of things targeted at postal voters generally missed that point that these were the most politically connected voters so (a) likely to vote and (b) likely to be more fixed in their persuasions.

In 2015 it was interesting to analyse a ward and find that there was a group of voters who voted in 2010, but not in any election since. And we had virtually no canvass data on those people. One thing that pointed to was that having been canvassed was something that caused people to be more likely to vote in local elections. (alternatively there were demographic reasons why they were less likely to be canvassed which made them less likely to vote). That – combined with some quite tight geographical targeting of postcodes with high levels of LD (or non-Labour) support – was a strong indicator of the people we needed to target most (basically if you voted in 2010, hadn’t voted since and lived in an area that was not Labour voting you were likely to vote in 2015 so needed strongly targeting particularly with squeeze messages).

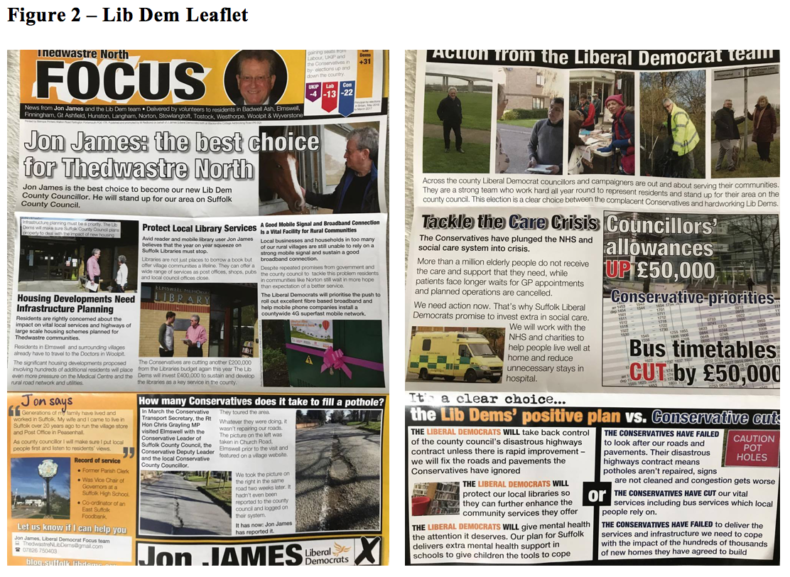

Looking at Rugby Borough elections over a number of years I came to the conclusion that just issuing a leaflet did nothing to increase the Liberal Democrat vote. A point worth noting from this example is that the leaflet appeared to refer to a candidate who had already been out and about – the leaflet might have reminded people that they had had previous contact with that individual. I would like to see another experiment done with a paper candidate who had just been parachuted into a ward with no history of contact with that ward.

Phone canvassing as such is not mentioned. Phoning non TPSed people is quick cheap, reaches lots of people and can be done from anywhere in the warm and dry when it is raining. One should be able to phone in the region of 50 people per hour and have conversations with 20 to 30. Phoning between 5pm and 8pm is the best time. It can easily be split between Postal voters and non- Postal Voters. Speaking to people on the doorstep is probably better but you can reach so many more people on the phone. How long would it take to bang on fifty doors? Of course non TPSed people are a sub section of the electorate but still worth targeting

I think the point about did they change their views is important as separate aprty research has indicated that direct individual conversations is the most successful way of getting voters to change their vote, so that “canvassing” in its broad sense is extremely important unless you’re in a very safe Lib Dem ward. Agree that phone is virtually as good as doorstep though it’s good to meet every voter face to face once if you can. Other research shows that people are more likely to trust people they’ve seen face to face – they get the non-verbal signals there.

Why are we not considering the two biggest recent demographic changes? One, that most of us are increasingly more likely to absorb stuff via social media (in the widest sense, including from friends) and less likely to pay attention to paper on the doormat. Recycling boxes by the front door also mean much more print just gets dumped. Two – housing changes increasingly mean young and middle-youth people move around rentals yearly, are less rooted in one community and their details, our data (and thus the targeting) less likely to be accurate. This may be truer in cities, but hey, they’re important!