Three unanswered questions about Peter Hain and Philip Green

The ability of a Parliamentarian to use Parliamentary privilege to break a legal injunction with impunity is both an important safeguard and a power easily open to abuse. Which is why it should only be used in exceptional cases.

Does the decision by Labour peer Peter Hain to name Philip Green as “as the man who prevented the Telegraph publishing allegations of sexual and racial harassment” fit the bill?

Despite the widespread media coverage of the decision, three key questions have been left mostly unasked, let alone answered.

First, the injunction was a temporary one, pending the resolution of legal hearings and still, for example, giving the Daily Telegraph the chance to make its legal case arguing for him to be named. What justifies breaking the temporary injunction rather than waiting until the next legal hearings had taken place and seen what their outcome was? If, say, a politician up for election was involved and polling day was due before those hearings, you can imagine a good answer to that question. But for such a dangerous power as over-riding a court ruling to be used, there does need to be such a good answer. What is it in this case?

Second, how carefully did Peter Hain consider the case before deciding to break the injunction? He says he did, yet he also says he wasn’t aware that a legal firm which pays him is central to the case. As that legal firm is named in the rulings so far, how did he both manage to consider the case closely and yet also miss his own potential conflict of interest? Add that to the speed with which Peter Hain made his decision – naming Philip Green within hours of the legal ruling – and this looks rather more like a rushed judgement that didn’t involve carefully checking the facts of the case first.

Third, and most importantly, two of the complainants against Philip Green had said they wanted him to remain unnamed. The role of anonymity in such complaints is often a controversial one – but again, what’s far from clear from what Peter Hain has said so far is why he took a decision that overrides the wishes of these two people. Again, it is possible to imagine circumstances in which over-riding such wishes might be the right thing to do (suppose, for example, there were 531 complainants and 529 demanded the person be named but 2 opposed it and moreover the person could be named in a way which continued to make it hard to identify that pair). But it says something pretty poor about how such cases are handled if over-riding the issues of those who made complaints is treated as a side-detail frequently omitted rather than central to the question of whether or not over-ruling the courts was right.

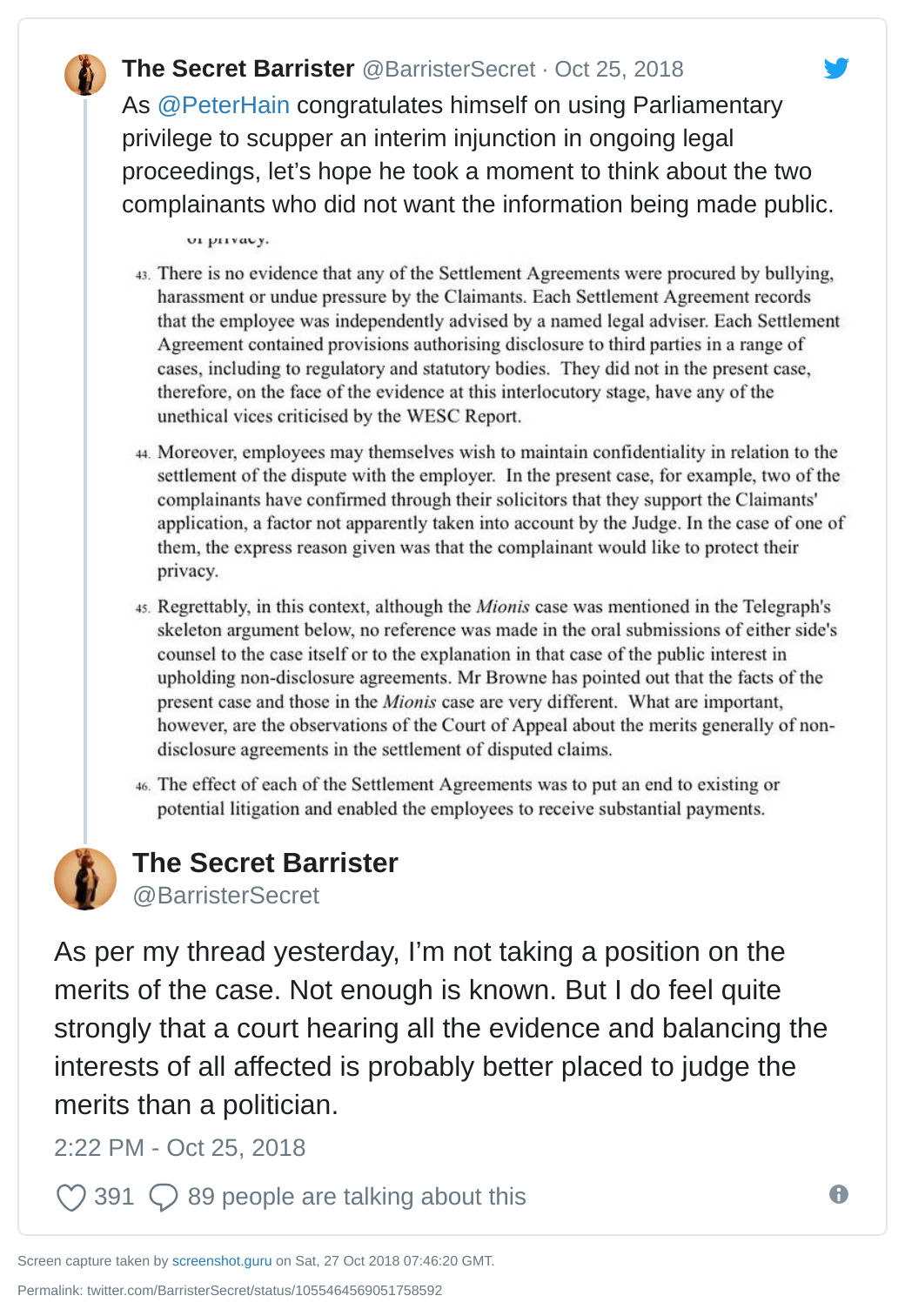

Or as The Secret Barrister put it on Twitter:

It’s not often that I disagree with Vince Cable, but I don’t think he was right to rush to defend Peter Hain’s action. I think the considered reaction by Dominic Grieve and Lord Judge were absolutely right.

It seems a rush to me but:

Perhaps Hain thought that (since the court had to think the outcome would be a ‘likely’ win for a permanent injunction to grant a temporary one) it would be better to shortcut the case rather than waiting until the court had set an undesirable binding precedent?

I fail to see why the wishes of some of the alleged victims not to see Green named were of relevance. (Obviously their own identities should be kept secret). If it were to be true that his behaviour was of such an unprofessional nature as alleged then the public interest lies in prospective employees knowing what they’re letting themselves into and the members of the company (shareholders) having a proper understanding of the nature of the management of their company*. The public interest isn’t in the freedom of the alleged victims to tell or not tell their story.

(* there should be a strong case, I believe, that the use of company funds to buy the silence of former employees on the subject of such management is in itself a misuse of funds by the directors, particularly if it relates to their silence to the shareholders. Or perhaps it should be fine for middle managers to be able to use their unit budget to bribe their hires not to tell senior management/HR on them?)

Philip: in response to your second paragraph, I’d expect that the reason some of the alleged victims wanted Green to remain unnamed is that they believe that the naming of him will mean their own identities are not kept secret – i.e. that you can’t remove his anonymity without also removing their own. E.g. if there is other information in the public domain that pieced together with news that he was the subject of such complaints and made NDAs with people means people can figure out who they were. (‘Oh that person who used to work for him but then left suddenly and always keeps quiet about their reasons for leaving…’, etc.)

I can imagine circumstances in which honouring their wishes may be the wrong thing to do. I fear however we’ve still got a very long way to go in taking the concerns of alleged victims seriously given how little weight most people seem to give to the explicit requests from two of them for Green not to be named.

I get that concern Mark, and my heart really does go out to them. But are you really suggesting you can imagine hypothetical circumstances (short of threat to life) where a court could objectively find that:

(a) disclosure of a persons abuse of power iro sexual harassment was objectively in the public interest

and (b) that three out of five victims wanted the name publicly disclosed

but the wishes of two other victims should nevertheless override the court’s determination.

Philip: I’d say two things in response to that – first that the very fact we have to get into such detailed speculation shows how much better it is instead to have the courts judge all the evidence and context and make a decision, rather than trying to second-guess hypotheticals that may, or may not, capture the relevant issues, and second – yes, I can – if, for example, the two in question are children (and it’s a normal part of our legal process to give children extra protection), the only way to protect their anonymity is to avoid naming the (alleged) criminal, and if that person has anyway been convicted of a similar crime and so the benefit in terms of publicity for reducing future risk has already been secured. That (I’m pretty sure!) isn’t the case in this circumstance, but rather shows how there are cases where it could be the right thing to do – the only way really to know is to know the full facts of the case. Neither of us do – but nor, it appears, did Peter Hain before he decided he would over-ride an interim court ruling.

I find it bizarre that these are still accusations, and yet the call for him to be stripped of his knighthood is already doing the rounds. Perhaps there should be two rules 1) innocent til proven guilty(I thought we had that one) and; 2) if guilty, part of any sanction should automatically be the loss of any title and associated privilege, as being clearly undeserved… now I wonder how many members of the Upper House are there still presiding over us despite having served a prison sentence..?

The use of injunctions is something only the well off can afford and like much of British justice is therefore unavailable to the rest of us. Whilst i have no doubt there are important principles at stake most of us will be seeing karma in the plight of Green and perhaps even some delight that someone who has patently treated many others badly including BHS staff might himself be suffering a degree of discomfort.

The first step in solving any problems is to abolish the unelected House of Lords.

Arguing about the rights or wrongs of Peter Hain using parliamentary priviledge is really a minor issue in so far as its impact on most people. It is a diversion from the fact that only the rich can take advantage of legal injunctions. Such injunctions should only be issued in the rarest of circumstances and should not be available to merely avoid the rich and/or powerful being subject to embrassment. Moreover, while are legitimate reasons why employees may sign confidentiality agreements with their employer, protecting the employer from a claim of racial or sexual harassment should not be one. There is also a difference between the parties to an agreement breaching its terms and a third party reporting what it has learnt. If the source of the information was the employee then it is open to the employer to sue the employee for bteach of contract. However third parties should not normally be prevented from publishing the information they have obtained.