Who is Ed Miliband?

Authors of the best accounts of the New Labour years delved deeply into the rival Brownite and Blairite versions of events before coming to their own conclusions. Those who did not frequently ended up with embarrassingly lopsided and inaccurate accounts.

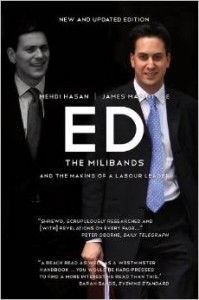

Mehdi Hasan and James Macintyre, the authors of Ed: The Milibands and the making of a Labour leader, have avoided making the next generation’s version of the same mistake by talking to both sides of the Miliband family, even returning more than once to the conundrum of when Ed told David he was going to run against him for leader. The different versions of events from across the brotherly divide flatly contradict each other and, as the authors rightly point out, that is not a promising sign for a harmonious future.

Aside from balancing these conflicting camps well, the book also handles skilfully the fact that with such a new leader to write about, there is so far very little hindsight available with which to make sense of his earlier career. Yet due to the book’s balanced approached, whether Ed Miliband is a success or a failure, the explanations are likely to be found in the book. Most notably, it recounts several of the high profile campaigns he has run, from student politician through to Cabinet minister, which have two themes in common: successfully involving a large number of people yet also failing, in the end, to deliver the main objectives with Ed Miliband eagerly trying to describe failure as success. Whether he should succeed or fail, that is a record that future biographers with the advantage of hindsight will merrily return to in order to give their explanations.

Aside from balancing these conflicting camps well, the book also handles skilfully the fact that with such a new leader to write about, there is so far very little hindsight available with which to make sense of his earlier career. Yet due to the book’s balanced approached, whether Ed Miliband is a success or a failure, the explanations are likely to be found in the book. Most notably, it recounts several of the high profile campaigns he has run, from student politician through to Cabinet minister, which have two themes in common: successfully involving a large number of people yet also failing, in the end, to deliver the main objectives with Ed Miliband eagerly trying to describe failure as success. Whether he should succeed or fail, that is a record that future biographers with the advantage of hindsight will merrily return to in order to give their explanations.

Where the book struggles rather more is in explaining quite what Ed Miliband really believes. The book goes through various occasions where it has been claimed he was critical of the Blair/Brown governments, weighing up the evidence and concluding that on several occasions he did indeed dissent, albeit usually very privately. Yet in parallel with this account of a thoughtful critical friend, the book also presents an account of someone who was extremely loyal to Gordon Brown, opposing plots against him and insisting that he should not be ousted before the 2010 general election. Ed Miliband appears to have been at the same time both more critical of Brown than other Brownites yet also the most loyal of the loyal to Brown.

Ed Miliband appears to have wanted to both have his cake and eat it. This unresolved question does at least explain the curiosity of the book finding plenty of evidence of Ed Miliband thinking of standing for Labour leader well before a vacancy arose, yet also when it came to it being horribly unprepared and having to fight through organisational chaos for several weeks. It was as if he had been both wanting to stand yet also not want to do so – hence talking about it yet not preparing for it.

More positively, what comes through clearly is how important being nice has been to his political career. A large part of the reason he was able to present himself in the leadership contest as the man to leave behind the old Blair-Brown struggles, despite having been such a central Brownite figure, is that – to put it in an old fashioned way – whilst many of his colleagues spent their years in governments swearing at others, he spent the years showing good manners.

One area the book does not shed any light on is the almost comical lack of preparedness for hung Parliament negotiations by the Labour Party. Despite many in the party for a long time thinking their best hope was to be the largest party in a hung Parliament, when a hung Parliament did occur, Labour was unprepared for negotiations. Ed Balls only discovered shortly before the first meeting with the Liberal Democrats that he was on the negotiating team, for example, and his preparations for that involved a quick chat over a cup of tea just beforehand with Peter Mandelson.

Yet Ed Miliband should have been central to a proper preparation process. As the prime author of the manifesto, he should have been thinking – however infrequently – about what might or might not work in a hung Parliament. As one of Gordon Brown’s closest advisors, he should have been reminding the then Prime Minister that a hung Parliament would then require talks and talks require preparation.

His failures in this regard are not simply a matter of historical curiosity because if the truth is that he (like many others) was so lost in traditional Labour tribalism that he failed to grasp a hung Parliament wouldn’t simply be a matter of Gordon Brown telling other parties what to do, then how likely as leader is he to be at getting the pluralism he occasionally talks about right?

That said, the authors are by no means unthinking apologists for Labour and make the powerful point that in one respect the die is already cast for Ed Miliband’s leadership: during those early days when he could set the public’s perception of him there was no single iconic picture. Contrast that with David Cameron and the controversial but (in part for that very reason) successful huskies photograph.

As they add, “Mischievous critics of the Labour leader have suggested there is such a snap: Ed hugging his defeated brother … The perceived void over what Ed stands for risks being filled by a definition probably most recognisable to the public: that he is the man who ‘shafted’ his brother”.

At this early stage in his leadership any book can’t hope to answer for sure the question of whether Ed Miliband’s leadership will ever amount to more than that. But this book does a good job at filling in the background against which we can all speculate.

Buy Ed: The Milibands and the making of a Labour leader by Mehdi Hasan and James Macintyre here.

Leave a Reply