If you want to understand modern government, understand the Office of the Public Guardian

The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) neatly encapsulates much of how modern government is run, its weaknesses and the problems our democratic systems face in trying to control or improve bureaucracy.

The Office of the Public Guardian was created for the best of reasons following the 2005 Mental Capacity Act in order to administer a new Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) process by which people can lay down what should happen to them and who can make decisions for them if they lose the ability to decide for themselves. The OPG is, in theory, an accountable public body with annual reports, performance standards laid down by the Ministry of Justice and its operations open to questioning in Parliament.

But it also reveals the dark side of modern government.

Complicated paperwork

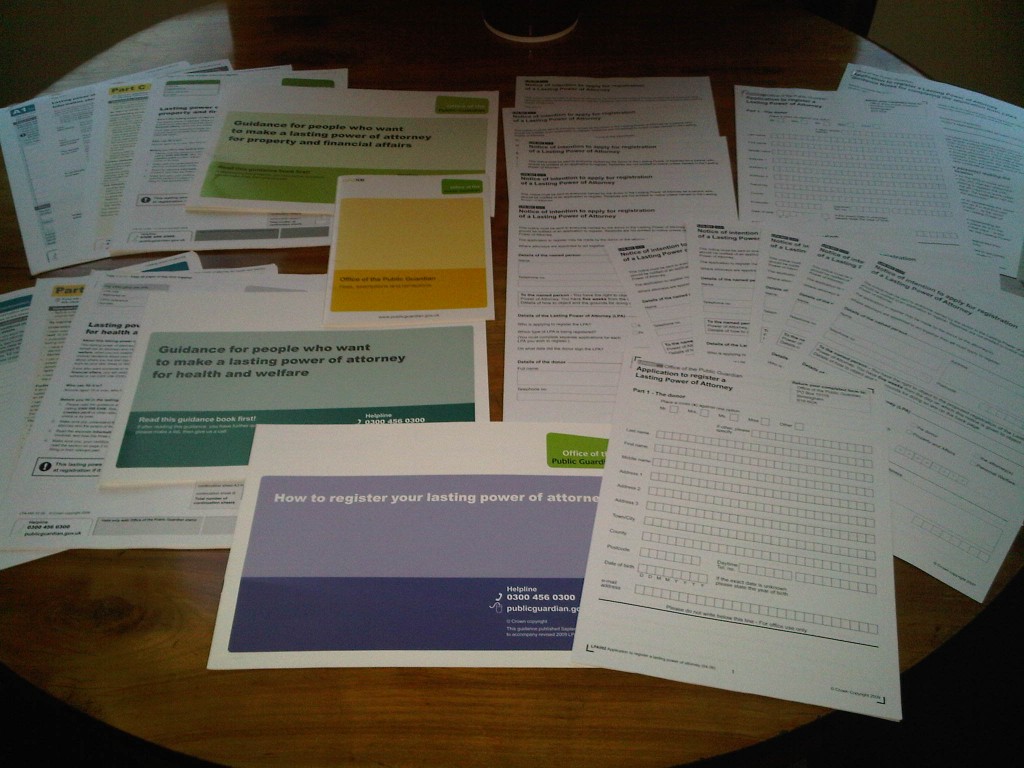

The intents behind the 2005 act have spawned a large and complicated bureaucratic process. As I have blogged about my own experience of the paperwork, it is voluminous with people being told to read 88 pages of guidance booklets before even starting on filling in the paperwork for Lasting Powers of Attorney:

Once the paperwork is completed, there is a charge of £240 to register it (though with discounts available to some).

The paperwork itself fails to impress with several minor errors and inconsistencies, but more fundamentally, much of the paperwork is duplicated, because the law lays down two separate processes (one for health and welfare issues and one for financial issues). Rather than imaginatively address the problem – such as by producing one combined booklet which, for legal purposes, counts as two, or by public lobbying to amend the law – the Office of the Public Guardian seems to sit by content with such duplication.

For a process aimed at helping people in highly vulnerable situations, complicated paperwork and difficulties thrown up by legislation that was not drafted with simplicity in mind is highly misplaced – but is also very typical of the processes thrown up regularly by modern government and legislation. Just think of the problems with the tax credit system or the huge increase in the volume of tax regulations.

Money for lawyers

The legal profession has gained from the process because the complexity means it has all become another service for lawyers to sell. Lawyers can say with a clean conscience, “This is an important process, but there is lots of paperwork so perhaps you should pay me to sort it out for you?” Yet generating revenue for the legal profession is unlikely to be top of anyone’s list of priorities (even, to be fair, that of lawyers). Again though the OPG – good intentions resulting in money spent on lawyers – is typical of a wider trend in modern government.

In addition to the issues of complexity and legal expenses, the Office of the Public Guardian raises questions about how Parliament exerts control or influence over arms of the state’s bureaucracy. The OPG is accountable to Parliament, with an annual report published (alongside a written statement from ministers as in 2008) and key performance indicators set down by ministers and put before Parliament.

Questionable performance standards

However, as this version shows, the performance standards set should be a matter of controversy. The standards require the OPG to cover its costs from its charges and to process paperwork, deputy powers and its investigations quickly. Those are all admirable aims, but missing are aims such as having easy to understand systems (e.g. with a performance indicator tracking what percentage of non-lawyers who completed the forms were satisfied with their design).

Instead, the performance indicators promote a very closed, almost elitist system: as long as the processes are running, it doesn’t really matter what the public thinks of them or what proportion of those who might want or need to use the processes are being reached.

The figures from the OPG suggest that this has indeed ended up a system for the benefit of only a very small number of people, with just 6,000 applications to register health and welfare Lasting Powers of Attorney and 22,000 applications to register property and affairs LPAs between October 2008 and January 2009. Although these numbers are higher than predicted at the time of the Mental Capacity Act, the OPG itself is very bullish about how its services should be applicable to a very wide number of people:

We have an important role to play in helping people plan for the future in the event that they are no longer able to make decisions about their health, welfare, property and finances for themselves. No one can predict when this time might come and it is one of our key aims to raise awareness among younger people of their ability to make a Power of Attorney to safeguard their future, in the same way they might write a will or contribute to a pension fund.

How should costs be covered?

Moreover, should the OPG’s full costs be met by charges levied on users? Across the public sector, there is a wide range of practices, from free at the point of use via partial charges to full cost levied at the point of use. All have their pros and cons which vary depending on the exact circumstances, but in the OPG’s case, it is certainly plausible that the wider costs, both monetary and non-monetary, should be taken into account. For example, would lower charges result in more widespread use of the system and as a result less legal action, freeing up judicial time for other matters?

The fees were cut after a 2008/9 review, but that was simply on the basis of revenue exceeding costs rather than a consideration of wider issues about take-up rates and the true full cost to society.

Lack of Parliamentary interest

Looking through Hansard, the Office of the Public Guardian rarely features, except as part of wider questions about how much government bodies spent on Christmas decorations and the like. The specific role of the OPG goes almost undebated, and I have not been able to find any debate on either its performance indicators or annual reports. There is a similar lack of coverage from political parties more widely and from think tanks and the media. Neither the Conservative nor Liberal Democrat websites return any hits for “Office of the Public Guardian” for example.

Some MPs show a brief interest in its workings. The number of applications quoted above comes from a written question tabled by Lib Dem MP Paul Burstow and Conservative Dominic Grieve tabled a question which unearthed a disturbing pattern of a steadily growing volume of complaints about the Office of the Public Guardian. Conservative MP Ian Taylor too has put some pressure on with a written question about the time taken to process paperwork as have Andrew Selous (Conservative) and Annette Brooke (Lib Dem), while Tom Brake (Lib Dem) asked about staffing levels. These examples and a smattering of others are, however, one-offs. A brief piece of interest from an MP and then silence in Hansard resumes.

The OPG’s latest annual report itself makes some very positive noises about how it is improving (though that’s perhaps to be expected), including an impressive reading third-party endorsement.

Will MPs and ministers know enough to make the right decisions?

After the next general election, whatever the result, ministers – and MPs who hold them to account – should have to make decisions about whether or not the OPG is improving, and fast enough, whether some of the broader principles touched on in this piece have been got right and even – given it is an executive agency of a department and therefore one of those new bodies so often included in stories of how government bodies and quangos have proliferated – whether or not the OPG should be abolished.

I say “should have to make” these decisions because, with the apparent lack of any detailed interest in the Office of the Public Guardian from MPs, think tanks or the media it will be easy for such decisions to be let slide.

And it’s all a salutary reminder that when parties make broader statements about the spread of government bodies how little is usually known about the actual bodies being discussed. Broad principles are necessary but so too is detailed knowledge if those principles are to be turned into effective policymaking rather than ignorant shoehorning of everything into preconceived solutions.

These comments on OPG are fair and terrible. There seems to be no energy to remove parasitic bureaucracy such as this. It is just as burdensome as direct taxes. I have tried asking my MP about his views on excising the burden of OPG in current cuts. I don’t think he had heard of it. He is Exchequer Secretary, HM Treasury. This is how cuts fail us. OPG was a worthy but misguided and expensive and alienating attempt to improve on the simple, inexpensive and adaptable “Enduring Power of Attorney” available from local solicitors. It was a mistake which should be reversed if our legislators genuinely cared anything for the burdens laid on tax-paying citizens. If EPAs were open to abuse and misuse, that could have been addressed in other ways. Now people are exposed in the worst possible ways by not being covered with one. Do we actually know what has happened to the number of powers of attorney established? Has it been compared to the growth in dependents?