General Sir Richard Dannatt’s verdict: more cash, more time please

General Sir Richard Dannatt’s memoir of his time in the British army manages somehow to be both fascinating and banal.

General Sir Richard Dannatt’s memoir of his time in the British army manages somehow to be both fascinating and banal.

Fascinating because of the detail he provides to back-up his severe criticism of Ministry of Defence civil servants and politicians, Labour ones in particular but Gordon Brown above all, for failing to fund the army sufficiently for the jobs they demanded of it. Banal because, despite his long experience of counter-insurgency and peace-keeping operations starting with Northern Ireland in the 1970s, his repeated message through the book is one of ‘give the army more money, give the army more time’.

The contrast with the US army and the way, for example, it has massively altered its counter-insurgency approach under General Petraeus is marked. Resources and time certainly feature in the lessons learnt by the Americans, but are very far from the whole picture. The picture Dannatt paints of the British army by contrast is, in this respect, unintentionally a deeply unflattering one because it gives the appearance of an army looking over the last 40 years and pointing the finger at others rather than asking questions of itself.

In fact, the British army has been rather smarter than Dannatt’s account gives out, but how it has learnt the lessons of its mistakes such as those in Northern Ireland or tries to meet the continuing challenge to ensure that soldiers do not go violently out of control in the stresses of counter-insurgency are not stories told in this book.

The one significant area of army error Dannatt does concede in the book’s closing stages is that the army’s doctrine of “Go first, go fast, go home” was a wrong one. But we are left wondering whether some of what he blames politicians for is really the result of the army giving poor advice to those politicians based on its faulty doctrine. If the army’s own doctrine wrongly emphasised getting out of conflicts very quickly, was it really just politicians who are to blame for having planned and resourced the army on the basis that it would get out of conflicts quickly?

Yet Dannatt in other respects show a shrewd mind, particularly in his understanding of how counter-insurgency operations are both political and military questions. As he writes of his time in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, “If I found politics and the military hard to separate over the years, perhaps some might understand that the crossover goes back a long way.”

The book is written in a plain style, with a sufficient smattering of military jargon to give a taste for how rampant acronyms are in the modern military but without having so many as to confuse the casual reader. The account is regularly punctuated by name-checks for those held particular commanding posts, as if out of a sense of duty Dannatt often feels a responsibility to credit them.

The names of soldiers who were killed often feature too, sometimes movingly and always as a reminder about the human reality behind discussions of army deployments, resources or campaign outcomes.

Talking of his time peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia and the TV reports from the likes of Martin Bell, Sir Richard Dannatt observes how “the necessary though unspectacular detail of our mission was far less important to the editors back home than the prospect of some bloodshed. That always got people excited … If we, the military, are to succeed in these difficult missions, the media have got to be prepared to carry some ‘boring’ stories to record the progress that we are making”. In other words, he too feels that the media’s concentration on ‘the kinetic stuff’ paints a very misleading picture of what is actually happening in peace-keeping and counter-insurgency operations.

Despite these criticisms of the media, he also talks about how he deliberately used the British media to argue his corner for army resources, sometimes very successfully, such as over pay, and sometimes running into controversy for speaking out. This part of the book leads to the most moving sections, where he talks of the awful conditions many injured soldiers were left in and the work his wife and he have put in to raise charity funds to remedy this.

In all, the book is – perhaps like Dannatt’s own career – solid and competent. It offers much in the way of detail about how he believes politicians got it wrong, but little in the way of insight into the way the army should be organised and operate.

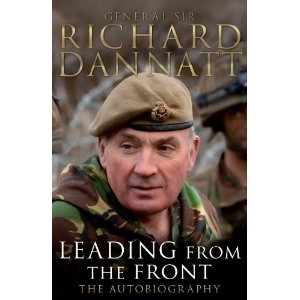

You can buy Leading from the Front by Sir Richard Dannatt here.

Leave a Reply