Three unanswered questions about Peter Hain and Philip Green

The ability of a Parliamentarian to use Parliamentary privilege to break a legal injunction with impunity is both an important safeguard and a power easily open to abuse. Which is why it should only be used in exceptional cases.

Does the decision by Labour peer Peter Hain to name Philip Green as “as the man who prevented the Telegraph publishing allegations of sexual and racial harassment” fit the bill?

Despite the widespread media coverage of the decision, three key questions have been left mostly unasked, let alone answered.

First, the injunction was a temporary one, pending the resolution of legal hearings and still, for example, giving the Daily Telegraph the chance to make its legal case arguing for him to be named. What justifies breaking the temporary injunction rather than waiting until the next legal hearings had taken place and seen what their outcome was? If, say, a politician up for election was involved and polling day was due before those hearings, you can imagine a good answer to that question. But for such a dangerous power as over-riding a court ruling to be used, there does need to be such a good answer. What is it in this case?

Second, how carefully did Peter Hain consider the case before deciding to break the injunction? He says he did, yet he also says he wasn’t aware that a legal firm which pays him is central to the case. As that legal firm is named in the rulings so far, how did he both manage to consider the case closely and yet also miss his own potential conflict of interest? Add that to the speed with which Peter Hain made his decision – naming Philip Green within hours of the legal ruling – and this looks rather more like a rushed judgement that didn’t involve carefully checking the facts of the case first.

Third, and most importantly, two of the complainants against Philip Green had said they wanted him to remain unnamed. The role of anonymity in such complaints is often a controversial one – but again, what’s far from clear from what Peter Hain has said so far is why he took a decision that overrides the wishes of these two people. Again, it is possible to imagine circumstances in which over-riding such wishes might be the right thing to do (suppose, for example, there were 531 complainants and 529 demanded the person be named but 2 opposed it and moreover the person could be named in a way which continued to make it hard to identify that pair). But it says something pretty poor about how such cases are handled if over-riding the issues of those who made complaints is treated as a side-detail frequently omitted rather than central to the question of whether or not over-ruling the courts was right.

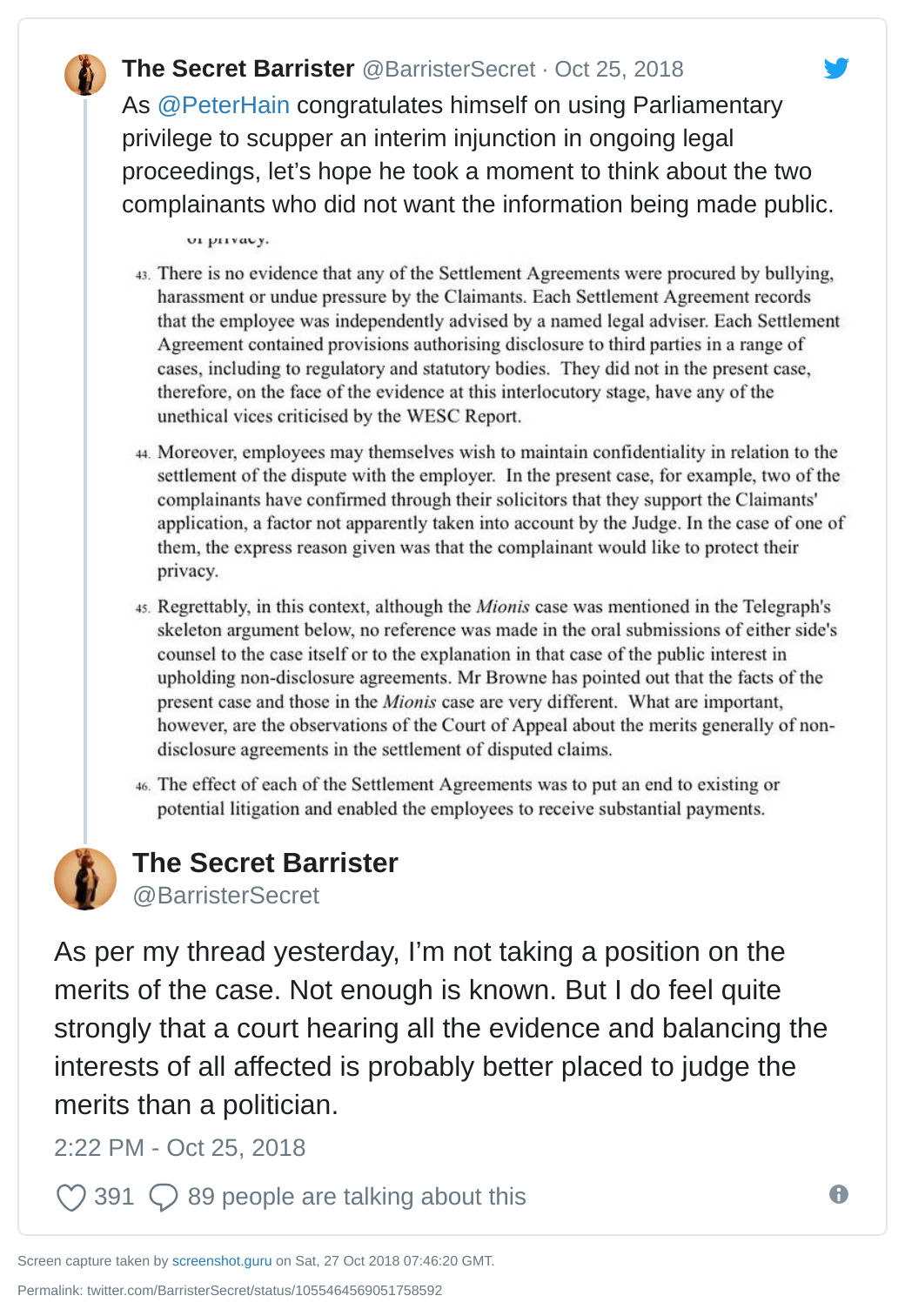

Or as The Secret Barrister put it on Twitter: